Hampton U. Resists Demand to Return Statue

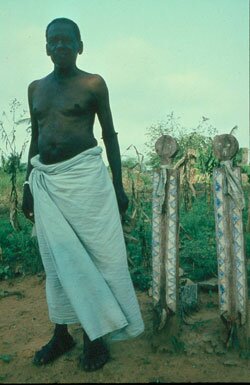

Hampton University continues to hold an African statue nearly three months after receiving a letter from the National Museum of Kenya demanding its return. The museum contends the statue was stolen. Hampton museum officials say they are still investigating how the blue-and-white kigango statue was acquired and will not return the statue until they are convinced it was stolen. Hampton has obtained a letter from Ernie Wolfe, a prominent African art dealer in Los Angeles, who said he purchased the statue legitimately. Hampton possesses a kigango that originally belonged to Kalume Mwakiru, a Kenyan villager who died in 1987. His statues were stolen in 1985, about two years after he erected them. Although there is evidence that the kigango once belonged to Mwakiru, Hampton officials say they are not sure it was obtained illegally. “There is no question that the statues were stolen,” said Monica Udvardy, a cultural anthropologist and an associate professor at the University of Kentucky. “This single case illustrates what is a growing social problem.” Udvardy visited Mwakiru's village in 1985, two years after Mwakiru built and erected his vigango, the plural form of "kigango." At the time, Udvardy was working with the Mijikenda people, and she took a picture of him next to the statues after interviewing him for two hours. Mwakiru had vigango built and erected in 1983 to memorialize the deaths of his brothers, Udvardy said. A kigango is sculpted as part of a Mijikenda ritual memorializing the spirit of a male who has died, followed by a celebration. The Mijikenda believe the spirit of the dead would come back to haunt the family and the land if the kigango were not created. The cost to pay a sculptor, who must also be of the Mijikenda people, usually runs more than a Kenyan's annual salary, Udvardy said. A kigango is erected in an area where, once complete, it is never to be moved. Days after Udvardy left the village and had the film developed, she returned to give Mwakiru a copy of the photograph. He cried, she said, telling her he had been heartbroken because his brother's vigango were stolen. He asked Udvardy to promise to find and return them. "Vigango are what we anthropologists call inalienable objects," Udvardy said. "The equivalent in the United States would be the actual paper the Declaration of Independence was written on, or the Statue of Liberty." It wasn't until 1999 that Udvardy found one of Mwakiru's missing vigango. During an annual meeting of the African Studies Association, Udvardy spotted what she thought was Mwakiru's kigango in a slide presentation by association member Linda Giles. Udvardy stood up and interrupted the presentation. "It was one of the uh-huh moments," Udvardy said. "I recognized that statue and knew it was stolen." Once Giles and Udvardy compared and matched slides, they paired up with John Baya Mitsanze, a Mijikenda curator of the National Museum of Kenya, to find the other kigango. Together, they went through museum catalogs, and Giles and Udvardy eventually found the second kigango at Hampton University. International Business Management Inc., in Culver City, Calif., donated the kikango to Hampton after purchasing it from the Ernie Wolfe Art Gallery in Los Angeles. Wolfe said he has been to Africa 48 times and that such conflicts over ownership are a first for his gallery. He maintained the statues were not stolen. "I stand by where I am," he said. "I did my due diligence." Wolfe said he considered the quest to return the kigango a personal crusade of anthropologists and interpreted the significance of the object differently. He said the Mijikenda told him vigango were priceless at one time, but as their culture changed, so did the importance of the vigango. "Vigango are a sort of bridge to a modern time in society," Wolfe said. Wolfe said the Mijikenda use an agricultural technique called slash and burn, in which they burn old crops to make new ones. The village remains in its place until the land becomes unfertile and forces it to move. Wolfe said when the villages moved, the vigango remained. A group that did not recognize the statue would burn it or let it rot. On one of his trips to Africa, Wolfe said, he sat around a fire with the Mijikenda drinking palm wine, trying to learn more about their culture and beliefs. It was at one such gathering that Wolfe said he learned that these statues were used before medicine was easily accessible. Now, instead of praying to the spirits in the statues, people go to a doctor, he said. "These things had no value to these people until they had value to others," Wolfe said. "They were willing to let them rot in the forest until people offered money for them." After finding one of the vigango that Wolfe had purchased, Udvardy returned to Kenya in January in search of Mwakiru. She tracked his family to a mud-wall house with palm-tree ceilings, only to discover that Mwakiru died in 1987. However, his widow, Kadzo Kalume Mwakiru, was still alive and her jaw dropped when she saw a picture of the vigango, Udvardy said. After communicating with Kalume's family, Phillip Jimbi Katana, the National Museum of Kenya's director of coastal sites and monuments, wrote to Hampton and to Illinois State University demanding the return of the vigango on the basis that they were stolen. Illinois State has agreed to return its kigango. Yuri Rogers Milligan, Hampton's director of university relations, said Hampton has taken longer to make a decision to be sure that the vigango are with their proper owners. "Museums are guardians," said Milligan. "It's not an ownership game -- it's about finding the right place. Things like this are priceless." Milligan said a university group created to look into the vigango dispute has contacted the National Museum of Kenya and reported the group's findings to administrators and trustees, who will deliver the university's final response. Udvardy called the episode an example of neo-imperialism, or a way for the West to take more from Africa. "If you buy these things in the West, you are destroying cultural heritage," she said. "They are not only losing their cultural history to the West, they are losing a part of themself." Whatever happens, Wolfe said Hampton should keep the kigango, as a museum in a learning environment would. "I would not return them," he said. "They should be exhibitioned. They represent how humankind are more alike than different." Posted May 17, 2006 |

https://blackcollegewire.org/news/060515_hampton-statue/

|

Home | News | Sports | Culture | Voices | Images | Projects | About Us Copyright © 2007 Black College Wire. Black College Wire is a project of the Black College Communication Association and has partnerships with The National Association of Black Journalists and the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education. |