|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Email Article | Printable Page |

"Black College or Die" Is Part of the Game Plan

|

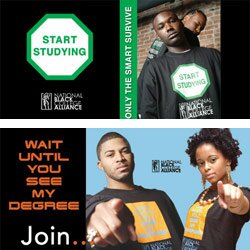

| Boston's National Black College Alliance has developed fliers and posters that feature street slogans amended with a positive spin. |

On a recent afternoon, George "Chip" Greenidge Jr. was sifting through e-mail, dressed casually in his corner office. It is a generous space that he fills with pictures of his students, African art and stray dollar bills. Greenidge is a tall, dark-skinned man with degrees from Morehouse and Harvard and 250 friends on the social networking Web site Facebook. The next day around this time, he'll be rubbing elbows with actors Morris Chestnut and Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson. Greenidge is a proud extra in a movie called "The Game Plan."

He has another couple of hundred friends on MySpace — and even more on AOL Instant Messenger. Asked how often he is on these sites, Greenidge doesn't flinch. "Daily," he replies. It is an e-reality fitting for a Boston socialite.

At 34, Greenidge is a Facebook user on a mission. He is the executive director of National Black College Alliance, a Boston-based nonprofit that helps high school students explore colleges and careers while inspiring them to give back through community service. His "friends" lists consists of a host of people who are members of the organization as students and volunteers. "We used to stay in touch the old school way —phone calls," he said.

|

| George "Chip" Greenidge Jr. |

Started in 2000, NBCA has a staff of five, but also "an army of volunteers and mentors," Greenidge says. Some of his "soldiers" will staff an event entitled "College Survival 101." It's just one way that Greenidge reaches out to members of Boston's professional and student community. In 2006, Greenidge and his organization mentored more than 300 students despite external challenges that affect the city at large.

NBCA's offices are in Dudley Square in the Roxbury section of Boston, an area long regarded as the cultural and economic heart of black Boston. Once the epicenter of the worst kinds of drug activity and violence, the area is undergoing a transformation, and NBCA is helping to lead it.

Joining the organization allowed Thony Ferdinand, a freshman at Morehouse College, to mentor students at Boston's Catholic Memorial, an all-boys high school. Ferdinand helps students complete federal financial aid forms and college essays, and tutors students with their homework. He went to a private school and saw a gap between what he learned and what was available to students in the city.

His students ask what it's like to go to Morehouse.

"They want to know about parties, mostly," Ferdinand says, laughing. "They want to know what the different schools have to offer. And they want to know about the brotherhood, too. They see the bond that we have, and how special it is."

But NBCA's task of recruiting and keeping students is not always easy. The organization thrives despite the challenges of supporting students in the inner city. Several come from broken families and have disadvantaged backgrounds. In 2005, Boston had 75 homicides — a 10-year high — and is on pace to exceed last year's figure. A 14-year-old was killed on New Year's Day. Shootings like these jolt residents because with 596,638 people, Boston's population is relatively small among major cities.

The events inspired Greenidge to start "Black College or Die," a campaign that will take 25 to 30 young people from the most troubled neighborhoods in Boston on several tours of black colleges.

Even NBCA has been affected by the rampant gun violence. Morehouse sophomore Michael Williams was shot in the face while riding in a car in Boston's Roxbury section. "I realized that my life can be taken at any point in time," said Williams, a political science major.

Williams said two people, both of whom are NBCA volunteers, helped him to challenge his ideas and encouraged him to put things in perspective during his recovery.

"My family here gave me the support I needed to understand things a little better, and gain a better sense of the state of the black community," Williams said. "I can't wait for things to change. It's up to me now, because there's a lot of work that needs to be done.

"It put the whole organization on alert that everyone is a target," said Greenidge. "We said that we needed to do more to take matters into our own hands and start being more active as mentors and volunteers. Here's a kid who did all the right things and someone is shooting at him? It didn't make sense."

Williams is one of the student organizers of NBCA's well-known T-shirt campaigns. Originally started in response to a popular T-shirt bearing the phrase "Stop Snitching," NBCA students wore and distributed shirts that read "Start Studying" and "Wait Until You See My Degree," playing off a not-so-educational expression in a pop song.

"The idea is to use urban youth culture to send positive messages. We can tell them about making the right choices, but it's our goal to put as many [of] the opportunities in front of them so that they can make the right decisions for their own career path," Greenidge said.

The organization has overcome perhaps its biggest challenge: trying to draw support in a city without a vast pipeline of African American leadership in politics, business and higher education. Places such as Washington and Atlanta not only have that pipeline, but well-known historically black colleges and universities, Greenidge said. In Boston, some students have never heard of HBCUs. NBCA is part of that exposure.

"I always wanted to go to an HBCU because I knew a black school would give me something I never experienced before," said Brittany Pennywell, a freshman at Hampton University from Lexington, Mass., a Boston suburb. Pennywell is a biology and mathematics double-major at Hampton University. "It's really good to see people who have gone to black colleges who can tell you what that experience is like. It motivates you to do better."

Greenidge and his staff continue to reach out to a growing network of college students and young black professionals, many of them HBCU alumni, who help volunteer and sometimes mentor NBCA students.

Greenidge is hopeful that support from the Charles Hayden Foundation will bring the nonprofit's model to cities everywhere, an accomplishment that has always been one of its goals.

"If an organization like ours can work in a city like Boston," Greenidge said, "then it can work virtually anywhere."

Posted Jan. 23, 2007

In News

N.C. Central's Ammons Picked to Lead FAMU

2 Kappas at FAMU Get 24 Months

Southern U. Weighs Prospect of First Black U.S. President

| Home | News | Sports | Culture | Voices | Images | Projects | About Us Copyright © 2007 Black College Wire. Black College Wire is a project of the Black College Communication Association and has partnerships with The National Association of Black Journalists and the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education. |